The Unintimidating Guide to Understanding P&L’s – Transcript

- by Holly Burton

transcript

The Unintimidating Guide to Understanding P&L's

Here to read instead of watch? Click through the headings to a section of the full transcript, or scroll away!

- What is a P&L Statement? (with Examples!)

- All the Jargon & Accounting Terms

- P&L Essential Check #1 – Is Profit Positive?

- P&L Essential Check #2 – Is it Profitable Enough?

- What Should Operating Income % be? (with Examples

- P&L Essential Check #3 – Are Expenses Too High?

- P&L Essential Check #4 – Do we Have High Enough Markups?

- Your 3 P&L Key Metrics (with Examples!)

- P&L Essential Check #5 – Are we Charging Enough to Cover Production?

- P&L Essential Check #6 – Are we Charging Enough to Cover Everything Else?

- What Else Can We Do to Improve Profit?

- P&L Essential Check #6 Part Two – Are We Charging Enough to Cover Everything Else? Another Useful Indicator

- P&L Essential Check #7 – How High are our Fixed Expenses?

- How P&L Statements Show Changes Over Time (with Examples!)

- Comparing Data – This Year vs Last Year & Plan vs Actuals (with Examples!)

- Summary – Essential Checks and Comparisons

- Links to Resources

(Edited for length and clarity)

Intro

My name is Dana Van Voorhis. I am a division president at a global food distribution company and I want to start today by acknowledging the land on which I live and work is the unceded territory of the Coast Salish people, including the territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations. I'm grateful for the opportunity to do so and to connect with all of you today.

A disclaimer: All of the numbers in the presentation today are completely made up. So, they're not based off of real companies; they are made up to make sense of what we're talking about today. If you're trying to read into them too much to try to figure out all the ratios that we're talking about, I'm not sure if they're real. It just works for our examples. Even the numbers that I'm going to reference in my own story and my own background are still not actual, they're more rounded numbers in my own personal story.

I'm also not an accountant. There are going to be words that I say that are not official accounting language, and that is okay. The good news about me not being an accountant and not coming from the finance part of the business means that I'm going to talk about P&Ls in non-financial language. I'm going to try to bring that down in a different way that is going to be a little bit more unintimidating and a little bit more friendly, and I hope that you get a lot out of this.

I have spent the last 11 years in food distribution and production. I started off my career, really, in the sales and marketing side of the business. I started off in marketing projects, moved over to overseeing our international business development for my company down in Southern California. When I was 26 years old, I got a big promotion. I was asked to move from the sales and marketing space from that Southern California company and moved to a different company in Southern California that was a sister company of ours as the director of business operations. I only had one actual job description with this role. It was to make the company profitable, but, as I just referenced, I have no financial background. I haven't actually ever taken a business class. I'm a science major from college so, I had to figure out these documents and all of this profitability –these financial statements—all on my own and I had to do it really, really quickly.

When I started, I had to attend my first senior management meeting. I was so excited, it was the first time I was invited, and this is what showed up on the screen. Now, don't try to read this. Lots of little numbers. All of the things that we present today will be a lot easier to read than this, but this is what came at me and I was so intimidated. How am I supposed to read this? There's so much going on. Oh my gosh, what am I supposed to do?

I also knew that this was going to uncover all the secrets that I needed to do my one job, which was make the company profitable. At the time, we were losing about $50,000-ish, and we really needed to turn this around. I needed to get friendly with something that looked very scary and intimidating and figure out how I could use all the information on this sheet to make our business profitable. Two months later, we were profitable. It was amazing. Our profit that first week was less than $100. It was quite small, but it was the first time this company had been in the black in a very, very long time and my boss and I celebrated like you couldn't believe. We went out to lunch, which we had to pay on our own dime because our company couldn't really afford to reimburse us.

It was really the big starting point of profitability for this company. We grew, and we grew, and we grew and about six months after I joined the company, we had all the bigwigs of our corporation come in. They wanted to know what we did to change our profitability; they wanted to know how the business was going. My boss and I were both new and they wanted to do a business review with us.

We had to put together a lot of different documents, and one of the things that I was asked to put together was a simple graph that showed our profitability before we arrived to today, every single week. That graph pretty much went straight up. I was presenting it, telling them what I did, and my boss's boss's boss's boss, the biggest of the bigwigs that were in this very intimidating meeting took that graph, and he looked at me and he said, "Dana, you're going to have a performance review coming up. And when you have that performance review, what I want you to do is I want you to take this graph, I want you to put it on your boss's desk, and I want to just say, 'You're welcome,' and walk out." That's how confident he was in what I was doing, and I didn't know at the time how important that meeting was, how important what I did was, because I was naive. I just was told I was supposed to make it profitable and I did what I was told I was supposed to do. That was really the jumping off point of my entire career.

I would never be where I am today at a very young age climbing that corporate ladder if I wouldn't have understood our P&L and I wouldn't have had the opportunity to dig into it and to figure out how to change the numbers on this great document that we sit and we look at every day.

What is a P&L Statement? (with Examples!)

I'm going to hopefully get you to the point that you understand the P&L, you know how to interpret your P&L, and hopefully even grow to love the P&L as much as I do. I promise it won't look as nearly as scary as this. We're going to work on demystifying this terrifying income statement and break this down into something that makes sense, that you can use in the future to impress your bosses just as much as I used to impress mine.

What is a P&L statement? A P&L statement, also known as a profit and loss statement, shows revenues, expenses, and profitability over a period of time. Really, it's asking you: Are we making money and how are we doing it? We're going to start with an imaginary chicken company. I know this is a very unusual example, but we're trying to make this as simple as possible. This company only does one thing. Most companies do a whole lot more than one thing, but this one is just going to take one-pound chicken pieces and sell them; one item, one thing, no company in the world makes it this simple, but this is going to help us really understand what they're doing and how these numbers work.

Feel free to follow along with the included spreadsheet as we work through these numbers. You'll see a bunch of different companies on them. We'll start with the first company, and we'll move on, but these numbers are provided for you. We sell chicken to grocery stores, and we sell these one-pound increments of chicken for $7.14. On your P&L, this is going to be what's called sales, or revenue. That chicken costs us $5.71. This is going to be known as the cost of goods sold, or the COGS.

When we subtract what we sell it for from what it cost us, we're going to get $1.43 and this is going to be our gross margin on the P&L. But, we have expenses. We have a building that we have to either own or lease, we have employees we have to pay for, we have packaging materials, we have a lot of different things. So, we have expenses. For every pound of chicken that we sell, we have $1 of expenses. This is called your total operating expense and when we subtract these two numbers from each other, we're going to see what we actually make –what our true profit is—which, in this case, is 43 cents for every pound of chicken. This is also known as your operating income or your profit. This is what you're going to be looking at for your simplified version of the P&L and these categories are going to be on most P&L statements.

All the Jargon & Accounting Terms

One of the fun things to note is that we have some jargon that comes out of P&Ls that we actually use in our day-to-day life, including the bottom line. That's really what we talk about with profit because, at the end of the day, it's what matters. It's the bottom line, but it also is what's at the bottom of the P&L statement. We also talk about the top line. We talk about sales or revenue—top line growth. This is because the sales line is at the top of the P&L.

“Sales” is what we sell it to our customers. “COGS,” or cost of goods sold, is what that item costs us from our suppliers. When we subtract those, we get our gross margin but, we also have expenses, our “total operating expenses.” Now, we subtract those and we get our operating income or our profit.

At the end of the day, what do we make? Just for fun, because we love to confuse everyone all the time, there are a lot of accounting terms. There are other terms that companies may use instead of some of these. Instead of “sales,” your company might put on their P&L “revenue or net sales.” Instead of “gross margin,” you might see “gross profit or gross profit margin.”

Operating income has a lot of terms. This is just a small smattering of them, but there's a couple different areas that you might see, including just simply, “profit.” So know if your P&L doesn't look exactly like this, all of these components are still there they just might be called something else.

Let's go back to this P&L statement. At the end of the day, we are making 43 cents for every single pound of chicken that we're selling. My question to you is: Is 43 cents per pound of chicken any good? Seems kind of small, but is that what we expect? Do we think it should be bigger? Let's see if maybe we can clear it up by looking at this at a larger scale. So instead of one piece of chicken that we sell, maybe let's look at all the chicken that we sell over an entire year. We're going to multiply everything out by the amount that we sell in a year, which is 35 million pounds and our numbers change a bit. Our sales are now $250 million. Our COGS, or cost of goods sold, is now $200 million. When we subtract those from each other, we get a gross margin of $50 million and our total operating expenses at $35 million. When we subtract those from each other, we get our bottom-line profit of $15 million, also known as our operating income. $15 million is a lot more than 43 cents, so is this company doing well? Yeah, this company is actually doing really well, but this isn't something that you're going to know without understanding our industry.

I have a systematic way of going through these P&Ls to take a lot of these meaningless numbers and turn it into a set of useful indicators so that you can run a successful business. There are seven essential checks that we want you to remember every time you look at a P&L, and they’re going to give you a lot of answers to understanding scary document.

P&L Essential Check #1 – Is Profit Positive?

The first check is just simply, is the profit positive? It's really what you want to know first because at the end of the day, we want to know: Is our company making money, or do we have to make some drastic changes? When we go back to our example, we can see right away. Well, $15 million is definitely positive, so we're going to mark this as green and say that this checks off our first check that we're looking at. But, is $15 million of profit good? Would it be better if it was $50 million? Would $1 million still be good?

We sell 250 million pounds of chicken. How much profit should we expect to have off that amount of sales? Really, we need another way of checking this to see if we're making enough money.

P&L Essential Check #2 – Is it Profitable Enough?

For this, we have a very handy metric or metric called operating income percent. Operating income percent is the total operating income, or profit, divided by the total sales. It's what percentage of your sales become profit at the end of the day? It's a very important metric that all of us are looking for that are analyzing our P&L.

If our total operating income or our total profit is $15 million, and we divide this by our total sales of $250 million. With that, we get 6%. So, is 6% operating income percent any good? Is 2% good? Is 1% good? Is 10%, 20%? What is good? Well, in our industry, 6% is great. In my industry, we expect an operating income percent of anywhere between .5 to 6% to really be on target for what we're looking for. But obviously, you're going to be wondering to yourself, "Well, what am I supposed to have for my company?"

What Should Operating Income % be?

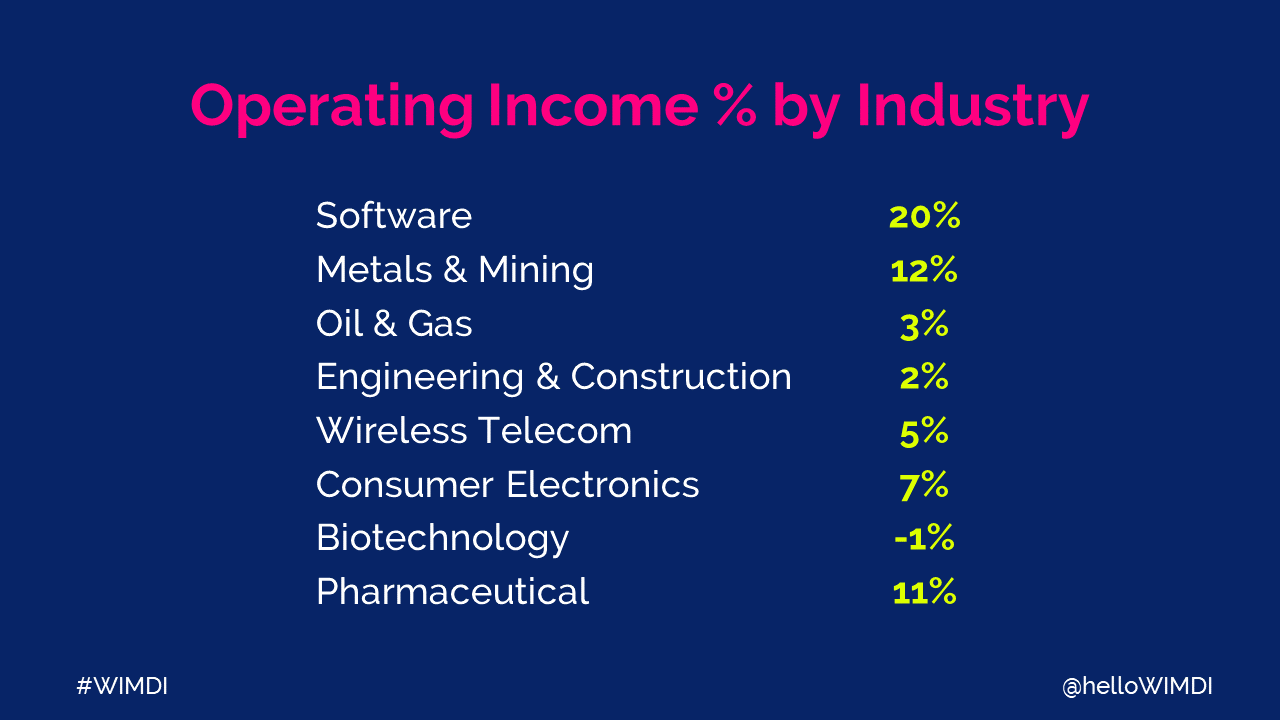

NYU has put together a really handy tool for everyone that breaks down the operating income percent that we expect by industry.

As you can see, software is at 20%, oil and gas down at 3%, biotechnology at negative 1%. They literally plan to be negative, and that entire industry is negative, which is incredible. There's a lot of variation between industries. If your industry doesn't show up on NYU's handy chart, you always can go to your CFO or your finance friends to ask them what you would expect for your operating income percent, or how much of your sales turn into profits at the end of the day, and what are the targets? And if no one can give you that answer, Google is always your friend.

This is where you see operating income percent or OI percent. It's always listed under your operating income or your profit and because that check number two was positive, we were within our range of .5 to 6%. We're going to mark this green and say that, yes, this did pass our check.

We've gone through the first two of seven checks. Is the profit positive, and is it positive enough? Or what is your operating income percent, and is that in the range you expect it to be?

So now, we're going to use a different chicken company, Imaginary Chicken Company Number Two, and we're going to have a different set of numbers for them. Their sales are going to be $300 million. Their COGS, or cost of goods sold, (what the chicken costs them that they're going to be selling) is $233.25 million. When we subtract those, we get a gross margin of $66.75 million. Then, we have our total operating expense of $76.75 million. And you may already see what's about to happen when we subtract those numbers to get our operating income (or profit) of -$10 million.

-$10 million isn't going to pass our first check: is the profit positive? When we add our operating income percent, we're also going to see a negative. It definitely doesn't fall into the .5 to 6% range that we are looking for. We're going to highlight that as red and it doesn't pass.

So why aren't we making any money? Well, it's very important to remember that profit is just how much we make minus how much we spend, or how much we have for gross margin minus total operating expense. At the end of the day, when you're talking about profitability, growing profitability, or why are you’re not profitable, those two metrics, gross margin and total operating expense, are going to be your key. How high is your gross margin? How high is your operating expense? And what do you need to do to change those?

P&L Essential Check #3 – Are Expenses Too High?

Are expenses too high? Again, we have a handy metric. Our metric is going to be operating expense per pound. Now, this is the total operating expense divided by the total pounds that we sell. We want to see if these numbers can get as low as possible. Lower expenses are always good. So, let's do the math. We have a total operating expense of $76.75 million, and we're going to divide it by $40 million or 40 million pounds. When we do this, we get that we have $1.92 a pound of this operating expense. Is $1.92 a pound operating cost any good? No. In our industry, we're looking at $1 to $1.50 a pound for our operating expenses.

Now, you're going to sit there and say, "My industry? We don't sell anything per pound. So how does this relate to me?" Well, every industry is going to be a little bit different. Every company can be a little bit different, but what you're looking for here is some kind of ratio of operating expense/ per unit of sale.

Let's say you're a mining company and you sell gold. It might be your total operating expense/ per ounce of gold that you sell. It might be that your company makes machines that other companies use, so it might be total operating expense/ per machine you sell. Or you might be service-based and it might be total operating expense/ per customer you have. You're looking at how you relate your operating expense to some relative unit of sale, and how high that is, or how low that is, and how it changes over time.

Operating expense per pound is what we're going to use, and that is going to be listed in whatever your metric is under the “total operating expense.” And because we said our range was $1 to $1.50 a pound, we're going to list this as red because $1.92 is quite high. Could we say that our total operating expenses are the reason why we're losing money? Maybe, but there's one other metric that we want to explore as well, because profit is gross margin minus total operating expense. We also need to be looking at whether we have high enough markups or margins? It's important to note that “markups” is another word for “margins.” We wouldn't say “gross markups,” but we often talk about what “the markup” to the customer is and that is the margin that we're getting.

P&L Essential Check #4 – Do we Have High Enough Markups?

“Gross margin percent” is just simply our “total gross margin” divided by our sales, or what percentage of our sales are represented by our markup. The higher the numbers, the better. We would love to charge our customers a gross margin percent of 90% and make a lot of money, but every industry is going to be a little bit different and some of your customers won't be able to pay for that large of a margin.

In this example, we have a total gross margin of $66.75 million, and we have total sales of $300 million. When we divide those, we see 22%. Is 22% gross margin percent any good? Yes. In my industry, we're looking for a gross margin of around 18 to 22%. Again, NYU has that handy tool that you can look up at the different industries and see what their gross margin average is. It won't really give you that range, but it will average that out.

We can see that gross margins are a lot higher than our operating income percent. Software is up with 72%. We see mining at 37%. We see that biotechnology, which loses money at the end of the day, is all the way up at 62%. It sounds like their expenses are quite high, and we can see this vary a lot by industry. This is where you're going to see the gross margin percent. You're going to see it right under gross margin as your helpful indicator. You're going to notice that all the indicators that relate to that top number (that you're always dividing by something like sales or pounds), they're always right under that metric that is associated. So here, it's under gross margin and we're going to list it in green because it's 22% and it passes our 18 to 22% range.

When we look at this, expenses are what we're going to need to look into a little bit more to see what we can do about changing our profit. We're going to make a little bit more room and we're going to actually look at our expenses in more detail. Most of your P&Ls will look more like this is going to look, where you see a total operating expense, but you see sub-categories that make up that expense and that's really helpful for when you're trying to figure out what's going on with your business.

In this case, we have our first line of expense as $7 million in warehouse expenses. In this industry warehouse, you're using it to both receive the chicken from your supplier and as storage before you bring the product into production. After it comes out of production, you're going to fit it back in the warehouse for storage before it’s shipped out to your customer. These are the “associated expenses.” It's that labour, that is, the shippers and receivers and the machines that you use in the warehouse –all of that is what makes up that total expense.

Then, you have production expenses. What we are doing in this company is we are buying big boxes of chicken from our suppliers; 60-pound boxes of chicken. We're opening those up, we're portioning it all out into one-pound increments and then packaging it into small packages that can be sold at the grocery store. A lot of our business is in this production area and a lot of our expenses are associated as such. So, $33.5 million of our $76.75 million is all in production, and that's really the labour that goes into opening those boxes and portioning out that chicken; it's the machines that do that work with the people and it's also the packaging associated with the process.

We have a transportation expense of $8.5 million. This is your drivers, your trucks, the maintenance for those trucks and gas. Then we have SG&A. This is also known as G&A, and it stands for sales, general, and administrative. If it's just G&A, it's general and administrative and is a lot of headcount expense. It represents your finance departments, your sales departments, HR, all of your executive's salaries and is typically one of your largest expenses of your line items.

Then we have occupancy expense, which is $2.75 million for this company. In occupancy, you typically see expenses that are shared by multiple departments, like the building that they're working in. So maybe property taxes, the mortgage –possibly rent for the lease or utilities. It's going to be costs that you need to spread out across the entire company. Those go into occupancy expense. So how do we improve this? Well, there are some questions that we want to ask ourselves. Which category is the biggest? Obviously, the bigger the category, the more you can influence that category and change it, and therefore the more opportunity you have. How changeable are the expenses? It's pretty hard to get rid of the building. Those leases are long. You may have to go through the process of selling and it doesn't happen overnight. So how changeable are those? How controllable are those expenses? These are things you want to ask yourself before you start tackling these different buckets.

Which has the more complex processes? How many more opportunities are there to maybe make something more efficient or better? The more complex the process, typically the more that you can play around with it to make them more efficient or cut some things down.

I'm going to put my hat on as someone who analyzes this and looks for areas that I might tackle first to try to see if I can reduce our expenses. What's your biggest expense? We see production and then we see SG&A –both of those are very big. Well, SG&A is a hard expense to change because it is really a headcount, so unless you're completely overstaffed, that one is one of the harder ones to change. I would probably put that on the back burner for the beginning of this, as well as the occupancy expense (the building), so you might not be able to affect that as much. In this company, it's quite a small building, so I probably wouldn't be going after it in the beginning anyways, but it is something that you would still look at over time. Are we using utilities that we don't need? These are questions we could look at, but, really, what I would be going after is the warehouse, production, and transportation expenses.

I would look at that bottom and say, "We're negative $10 million." Warehouse and transportation don't even make up $10 million independently, so I wouldn’t look there first, but more at our production expense because of how large it is. It's also quite a complex process, which we love, because there are more areas that we can look at in terms of efficiency.

I would also look at the expenses over time to see if we could keep moving those down and bring our OPP down to the range that we're looking for, which, in our case, is $1 to $1.50 a pound.

So, we have now gotten to four out of seven essential checks: Is the profit positive? Is that profitable enough? (The OI percent) Are those expenses too high? What's our operating expense per pound? (Or what is your operating expense divided by some unit of sale?) And do we have a high enough markups? How is our gross margin percent looking? And these three: OI percent, some kind of operations percent or operations per unit of measure and gross margin percent. These are really your key metrics.

As you get more familiar with your P&L, your eyes are going to go straight to this every single time and make sure that these numbers are in range. The reason why we're looking at this far more than we're looking at the actual numbers is that the actual numbers mean nothing without context. You may say $15 million of profit is great in that first example, but if we don't understand what that is compared to the amount of sales, it's meaningless. What we want to know is how much of our sales we drive down to profits, and that's why that OI percent is so important. It's the same thing with margin and expenses as well, and that's why these are the key metrics that we always focus on.

P&L Essential Check #5 – Are we Charging Enough to Cover Production?

What we're looking for is our production income to cover our production expense. Your company may not have production, but there might be a margin that has an associated expense that it would be offsetting, and we want to make sure that our income or production margin is higher than our expense because, again, profit is margin subtracted by the expense and you want to make sure your margin is higher.

You want your income, or your production income, or your production margin to be higher than that production expense. When we subtract these, we see that that production income at $3.85 million does not cover our production expense of $5.5 million. What we're going to do is we're going to change this to red and we're going to say, no, this did not pass check number five.

P&L Essential Check #6 – Are we Charging Enough to Cover Everything Else?

Are we charging enough to cover everything else? If we took out the production expense and we put it on the side, and then ask, "Does invoice margin cover all of our other expenses?" Invoice margin should cover our total operating expense minus our total production expense. If we look again, we see that an invoice margin of $8 million is definitely not covering all of our other expenses of $9.25 million, and we're missing that by about $1.25 million. So, that doesn't cover either but, we're not actually losing any money. We are making $250,000. So how does this even work? Well, we kind of lied to you. There are more margin buckets than it looks like here, and these margin buckets are a little bit different than the other two margin buckets.

Firstly, earned income. Earned income is my personal favourite margin bucket because it is very broad and a lot of things fall into it, and those things are operational efficiencies. Because I am a person that comes from a lot of operations background, I love operational efficiencies.

This could be an example that when we bought our chicken, the market price for chicken was $5, but we actually bought it for $4.75. We were able to wheel and deal. We were able to maybe make a huge buy, leverage something in our relationship with the supplier. And we were able to buy it for 25 cents under the market. What we might do is we might say, "We're going to discount the customer 15 cents a pound because we want to make sure that we're getting as many customers as possible. Obviously, we have a lower price than our competitors and we want to give the consumer some of that money back but, we're not going to give them the full 25 cents. We're going to keep 10 cents for ourselves, and we're going to put that 10 cents in this earned income. That's the good job from the buyers of what they were doing and their relationship with their suppliers. But, the thing is, is this doesn't happen every week. We're not always able to buy under the market. If we were always able to buy under the market, the market wouldn't be the market so it's not something we can always rely on.

It's also something that could be in production, where we decide that we have a yield and that's how we price our chicken. Well, if our supplier brings us skin-on chicken and we're making skinless chicken, we already know that the chicken skin should be about 10%, and the boneless, skinless chicken should be 90% when we buy it and the supplier sends us chicken that is cleaned up, and that skin is only 5%, well, we're actually going to make a lot of money because we expected for that skin to be 10%. That's how we priced it to our customers. Whereas, our suppliers might send us more skin than we'd expect. They might send us 15% skin and we're only expecting 10%. We priced to our customers on 10%, therefore we're going to have to absorb that cost.

We can also do some more efficient cutting in our room. We might cut better than we expected to cut, and that is all going to fall into this earned income. It's not money that we expect every single week. It's not something that we can always plan for, but it's always something that we want, always something that we're working hard for, because we earned it.

Then, we have this other “adjustments” category. A lot of this is inventory adjustments, and it might also be called “inventory adjustments” on your P&L. Often, you're going to see that when the inventory changes value. Sometimes, you have some spoiled product that you weren't able to use in the shelf life that it had, and so you're going to have to write that down. You'll hear the word “write-down” a lot, and that's really changing the value of your inventory. You're getting rid of that in your inventory. You're bringing your inventory value down, so you're writing it down and your operations forgot to scan a box and things happen.

You do a physical inventory count and you thought the product was there. You had it in your inventory, but you also have to write that inventory down. Once in a while, you'll see positives in other adjustments, but it's not that common. It's typically some kind of “write-downs.” So it's mostly a negative number, but as long as it's small, most companies understand that it's part of doing business.

What Else Can We Do to Improve Profit?

In our example, earned income is saving the day, right? Yeah. We absolutely would not be profitable if we didn't have that $5 million of earned income. When we look at it, we want to say, "What else can we do to improve profit?” If I can't rely on earned income every single day, I'm really going to have to make sure that I'm looking at this invoice margin and this production margin that seemed low compared to our expenses.

When we're looking at margins, we're going to look at the margin buckets that we have the most control over. And in this case, what you're going to do to increase your gross margin percent is either raise your production income or your production margin, or raise your invoice margin, or a combination of both.

P&L Essential Check #6 Part Two – Are We Charging Enough to Cover Everything Else? Another Useful Indicator

Are we charging enough to cover everything else…again? We have another handy indicator –our invoice margin percent. This is the total invoice margin divided by sales. For ex. $8 million of invoice margin divided by $100 million of sales, is 8%. So just like I've asked a lot today, is 8% invoice margin percent good? It's hard to know that without knowing the range and in our industry, 8 to 12% is what we're looking for. So, in fact, yes, it is in our range and we're going to be showing our invoice margin here just like the others underneath the invoice margin metric. We are going to list this in green because we are saying that, "Yes, we're okay with this." This hits our 8 to 12%.

"So, Dana, what are you going to do to increase this gross margin percent to increase your operating income percent?" Well, I would look at this in one of two ways. Invoice margin at 8% tells me that I still have some wiggle room there and remember with the first part of check six, we weren't covering everything else with that invoice margin. There's definitely room to grow there, but there's also production income, check five, that we also weren't covering. I have the decision of what I want to do first and personally, I would go after production income. That's because invoice margin is set by sales and it's a lot harder to execute change through someone else that's having that relationship with the customer and who is maybe wary about raising prices to customers, especially if they know we're in the range of invoice margin percent.

I'm going to go after production income first, and I'm going to look at that and say, "I have control over production income. Someone in my company does that's not sales. That's just where we're setting our prices for those production items." We would probably start there, but it's always important to note that any time you're raising your margins, it does mean that the customer is seeing an increase in price. You always have to be smart about how you do this and know that with your indicator of gross margin percent being under where you expect for the industry, that you do have wiggle room there. It's just scary wiggle room for companies to have because they're worried about margins, however, in this case your operating expenses are great –there's nothing else to cut—you just have to raise your prices to make more money.

Are we charging enough to cover production, yes or no? And are we charging enough to cover everything else? We have our handy metric of invoice margin percent to look at that and now, we come to our last company, our Imaginary Chicken Company Number Four. This chicken company has sales of $35 million. It has a cost of goods sold of $27.3 million. When we subtract those, we get our gross margin of $7.7 million. We have a total operating expense of $9.45 million. When we subtract those again, we get our total operating income or our profit of

-$1.75 million. We know it doesn’t pass check number 1; we are not profitable. And then, we're going to see OI percent, which is definitely not passing as well, -5%. It's not positive and it's not within the .5 to 6% by quite a lot.

We're going to add our OPP or operating expense per pound. We're going to see that this is very high, up at $1.89 and so we're going to also list this as red. If we add in our gross margin percent, we actually have good news here, it's 22%. Therefore, we know where we need to look. We need to look at our operating expenses. Now, we're going to go with the easiest one to evaluate here, because, as we learned about in check number five, production expense has an offset and margin with our production income. We're going to add these in, and we're going to see that our production expense is about $250,000 higher than our production income.

We know that we have at least $250,000 that we can try to cut in production expense.

When I look down at the bottom of the page at our operating income or our profit, I see that $250,000. It's not going to be enough, so we're going to need to look at some other categories and we're going to put production expense in red. What else are we going to look at? What's wrong? Well, I analyzed this imaginary company's P&L and there's something different here that we haven't seen on many of our other P&Ls. Some of your P&Ls will have a unit of sale like this, mine always do, but some do not. We haven't included them in all the examples, but here there is 5 million pounds of product.

If you remember that first example way back, there were 35 million, and that wasn't even the largest company that we had. 5 million pounds is quite small. It's important to note that there's a certain amount of expense that a company is going to have naturally, to be able to turn the lights on and run the business. You can't always cut all those expenses. You may need to look at the size of the company and evaluate whether those expenses make sense.

P&L Essential Check #7 – How High are our Fixed Expenses?

There are two kinds of expenses out there. There are fixed expenses and there are variable expenses. Fixed expenses are going to be there no matter how much or how little you sell, like all the costs associated with your building: your lease, your mortgage, your property taxes, your utilities—or the machines that you bought for that business that you need to be able to run it.

Then you have variable expenses; packaging is a variable expense. You use packaging when you're selling that product. You don't use it if you don't have the business to need it. That expense is going to go up and down with the volume of business. Same with labour costs, especially with operations labour, we get more labour when we need it, we reduce our labour when we don't need it. It's important to know how many of your expenses are fixed versus how many are variable.

When we are doing research, we're going to go talk to our finance team and we're going to find out that our SG&A or our sales, general, and administrative expense and our occupancy expense are all quite high for the amount of business that we're doing in this company. So, we have two options here. We can either fire everyone and move, or we can grow our sales. I always try to avoid any kind of firing or moving buildings. I only want to go up, not down in size. Let's hope that they decide to grow their sales.

That brings us to all seven of our essential checks that we talked about: Is the profit positive? Is it positive enough? OI percent. Are expenses too high? OPP or operating expense per pound, or maybe in your company's case, operating expense per unit of sale. Do we have high enough markups? Gross margin percent. Are we charging enough to cover production? Are we charging enough to cover everything else? Are our margins that we have control over covering our expenses? And then, how high are our fixed expenses compared to our non-fixed expenses, (our variable expenses)?

How P&L Statements Show Changes Over Time (with Examples!)

There's one last thing that we haven't talked about. We looked at this P&L statement in the very beginning, but we missed this part at end that shows revenue, expenses, and profitability over a period of time. Let's take Imaginary Chicken Company Number Four, (that either needed to grow or needed to reduce those high expenses) and look at them a year later. We're going to start with their 2021 numbers as well as 2022 numbers. If we go through our checks. We see that our profit is suddenly positive. Our OI percent is 1%, which falls into our .5 to 6%. Our operating cost per pound just went down to $1.47 a pound, which is well within our $1 to $1.50 and our gross margin stayed at 22% and is still green. So all of our metrics turned green, and it's really important to note that growth. We grew our pounds of product and that grew our profit. This signified how we moved those fixed expenses from being a huge part of our expenses to being a small part, and those variable expenses, (the ones that change when we have more business or less business) grew quite a lot with this.

Now, we're going to add a column and we're going to look at the difference (or variance). To get this difference, we take our 2022 numbers, and we subtract our 2021 numbers, and we can see how much we grew. It might be how much we shrunk in other cases, but we can deduce a lot of new things. First of all, we're able to see that our gross margin didn't change at all, which is incredibly impressive because most of the time, when you have to grow sales, you cut your margins to do so, and this company didn't do that. You'll also look at those two other expenses that we talked about before, SG&A, that had an excess headcount, they had too many sales on their books because they were trying to grow sales and they then forward invested in it. That didn't need to change. Their expenses related to the building also didn't need to change to bring in more business but, again, while these numbers help, they don't help us completely.

Comparing Data – This Year vs Last Year & Plan vs Actuals (with Examples!)

We're going to add one more column, and this is the percent difference. When you talk in financial language, or you hear your bosses, leaders or finance people talk, they often talk in percentages because it’s easier. We're going to add those as well. When we take the difference –Fiscal '22 minus Fiscal '21 and we divide it by the original date, which is Fiscal '21 we can see what the growth or shrink is. It was negative, so we see here that through our sales, pounds, cost of goods sold, gross margin, and our production expense all grew by 50% and therefore our business grew 50%, which is phenomenal.

We had associated production, row two, which kind of makes sense. All these pounds of product that we make are production pounds, so it makes a lot of sense that that would go up the same amount. We also see that our warehouse expenses and our transportation expenses only went up 20% instead of that 50%. With this information, we can see where we got more efficient with our business. Maybe those trucks that were going out weren't going out completely full, and now they are; we didn't have to buy 50% more trucks, we only had to get 20% more trucks and drivers. We can see when we look at the no change with SG&A and occupancy, the 20% with warehouse and transportation, that really brings a 50% growth in sales to only 17% growth in expenses, that that's really what changed everything here.

Our operating income has grown by $2.26 million, which is incredible, 129% growth, which is the largest here and exactly what we want to see. Our expenses didn't go up, so those margins just dropped right to profit. This is what you use to go to your boss and you tell them a great news story. "Boss, we grew by 50%. We were able to retain our margin. We were able to leverage these efficiencies in our operations to only increase our total operating expenses by 17%, and we grew our operating income by 129%. I am amazing, boss." That's what you're going to tell them and that's what they want to hear. They want you to tell them in their language, “What happened with this financial statement?” You can only do that by comparing these metrics over time, comparing last year and this year and showing what changed because a P&L statement at one point in time doesn't mean a whole lot when you don't have previous metrics to compare to.

There's one more comparison we also want to do, which is to look at a plan. Now, I am sure you have heard something about your company’s plan or budget for this fiscal year. All companies pretty much live and die by their budget plans. This is the jargon we use all the time. We're always looking at how we are doing, compared to the plan that we made a very long time ago. Well before the fiscal year even started, we committed to our investors, to our shareholders, to our bosses what we were going to do next year. You're going to see that your P&L statements are often comparing your actuals to what was planned.

Let's look at the Fiscal '22 that we've already done and then let's look at the plan. What did we plan to do? So clearly, this company expected to grow. They clearly had too big of a building. They invested in sales early and they knew that they were going to grow, but it looks like they grew a little bit more than they thought. So again, we probably need to look at more columns to make sense of this. We're going to add the difference and see that we still grew by $2.5 million more than we expected. Again, we kept our gross margin exactly where we wanted it to be and our production expenses actually did better than expected.

We had the same amount of production expense that we thought, so clearly there was some investment there and we also leveraged some great operational efficiencies as well. We can see that the action-only plan to have an operating expense of $1.50 a pound was exceeded, we were actually able to do a lot better there and thus, we were able to do better on our operating income percent. We were going to grow that by .5%, so we're very happy with that.

We love the percent difference as well, so when we add that, we see a couple more things. Well, we did better by 5% of our plan. We can see that maybe the warehouse expense was a little worse than we planned. Maybe we had a couple of forklifts that broke down and we had to invest in a little bit more. Maybe we had something else that we saw that we didn't expect to have, so we had to spend a little bit more there. We can still see that we grew 3% or 5% over our plan, but our operating expenses were still smaller at 3%, which was where we were able to see double the profit of what we expected. This was an amazing turnaround and your boss would be unbelievably happy.

Here's the good news or the story we're going to tell our boss. We're going to say that we had an aggressive sales growth plan, but we still exceeded it by 5% without discounting our margins to get this business. We did so by increasing our expenses only 3% for our 5% growth and improved our operating income by 1% over plan, or by 100%, or 94% of the plan to .5%. We doubled our overall profit to $510,000. You’re going to sit there and say, "We're amazing. Look at how amazing I am and look at what we did." Just like you want to compare to last year, you want to see the metrics you've come from. You are always going to be comparing to your plan because that is what your company committed to. It's always something that you're looking at.

We keep looking at our plan constantly and we look at it in multiple different areas: week-to-date, month-to-date, quarterly-to-date, yearly-to-date. How are we doing in each of those time periods compared to our plan at the same time? If we remember the big, scary document that we talked about in the very beginning, well, all this is a lot of mini P&Ls and while that might sound scary, it's really not. They all add up to each other. We're going to show you what they really mean and, again, we can't read these numbers, but this is what it's telling you.

It's telling you the daily actuals versus the planned daily numbers, which gives you your difference and your percent difference. You get your weekly. Same thing. What are the week-to-date numbers versus the planned numbers? Monthly versus plan. Quarterly versus plan. Half-yearly, possibly, versus plan. Year-to-date versus plan. What's your full year forecast now versus plan? And what was that year-on-year number? What was Fiscal '21 versus now Fiscal '22? And all of those have the difference and the percent difference on them. Not every company is going to look at all of these. I know personally, I only look at weekly, monthly, quarterly and yearly, but other people look at more. It really depends on your industry.

We’ve showed you a good smattering, but your P&Ls might not look this intimidating. They might look a little bit more manageable. We just have to look at this big, scary document, take a step back and just say, "This is just simply what we already talked about multiple times."

Summary – Essential Checks and Comparisons

Going back to the very beginning: sales are what we sell to the customer for, the total dollar amount. What are the COGS? They're what the chicken cost us to buy from our supplier. That's the “cost of goods sold.” When we subtract those from each other, we get the total gross margin and then, we have expenses –our total operating expenses. We now need to take the gross margin, subtract the expenses, and we’re going to get the total operating income or our profit.

We have seven essential checks. Check one is simply, is the profit positive? Step two, three, and four. These checks are key metrics. Remember them. Is it profitable enough? Operating income percent. What's the total operating income or profit divided by the sales? Are expenses too high? What's our total operating expense divided by unit of measure that we sell? In our case, it was pounds. In your case, it could be different, but you're looking at what your operating expenses are divided by something that is in sales. Do we have high enough markups? Gross margin percent. Gross margin divided by our sales. How much of our sales is our markup? How much money do we have to cover our expenses to get our profits? And this is just where they all sit? We talked about it. There might be subcategories under margin. There might be subcategories under expense. I would say most companies have those. They're not what's reported out to the public, but they are what you use in your internal documents, because you need to know what those are to be able to see what might look off and what you can affect.

Remember at the end of the day, profit is just how much we make minus how much we spend. It's the total gross margin minus the total operating expense, and if we remember that those are the three metrics that all relate to each other –when we're worried about profit—we know we can increase margin or decrease our operating expense, and that's how we're going to bring that profit up.

Then, we have a couple more things to look at once we identify if our issue is around expenses or margin. Are we charging enough to cover our expenses? If you have something like production income or production margin, is that more than your production expense? Is your invoice margin more than all your other expenses that it needs to cover? Is your invoice margin percent, (invoice margin divided by sales), at the right range? How high are our fixed expenses? Are our fixed expenses really high? If so, you’re almost always going to need to grow sales at that point. You want your variable expenses to be the big part of your expenses. Fixed expenses are hard to reduce, and you don't want a lot of them on your books, so increase your sales.

Then, we're going to need to look at this over time. We want to show what happened from last year; we want to know what the story is. If you are working on your P&L, you need to show where you started and where you went. When I talked about with that graph from my boss, all I was showing him was our operating income or our profit over time every week, and that was what was so incredible to him that he wanted me to show it to my boss as my entire statement for my performance review and just walk away. That is something that's very important. We want to show it over time –this year versus last year.

Our plan is king or queen of all of our business, it’s everything that we're looking for. It's what we talk about every single day. It's what all of our investors, our stockholders, our bosses are all looking at, so we want to know –how are we doing today versus our plan? What did we plan to do, and are we achieving that plan? And we look at that over time. We look at it weekly, hopefully. We look at it monthly. We look at all these different metrics so that we can see how we've affected our P&L over time. Is our gross margin growing or is it shrinking? Is our operating income growing or is it shrinking? Are our expenses growing and shrinking? And we are able to see that in one, not-so-scary document anymore.

I hope you feel the happiness and joy that I do whenever I see this, now, after all of these numbers and this very long talk, which was probably a lot of information coming into your brain. Just know that this P&L hides all the secrets of your business! This P&L tells you where you need to go next. It's not going to teach you how to do it, but it's going to help you go in the right direction and sometimes, you're going to have to try a couple of different things. Sometimes, all of your indicators are going to be in the red and you're going to have to affect a lot of them, but this is how you're going to take your career to the next level. This is how you're going to knock the socks off your boss, like I did to my boss's boss's boss's boss all of those years ago. And honestly, this is how I have succeeded in my career and I know that you can succeed in your careers the same way, too. So get comfortable with this document. It is your best friend and your best tool. And I hope that after today, you feel a lot better about it, and it feels a lot less intimidating.

Links to Resources

Follow-Along Spreadsheet with all the Math & Formulas

Financial Benchmark Data

https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/datafile/mar

More Fun Stuff!

If you loved reading this transcript, you might like to watch the video or learn more about our amazing speaker! Check it out: