Be a Good Rebel at Work – Transcript

transcript

Be a Good Rebel at Work

Here to read instead of watch? Click through the headings to a section of the full transcript, or scroll away!

(Edited for length and clarity)

Intro

I'm Carmen. If you're curious about my heritage, I was born in Puerto Rico and I went to high school in Texas, so I like to say I'm Puerto Rican by birth and Texan by nationality. I spent 32 years at CIA, where I ended up being the senior manager of analysis. We'll talk a little bit more as we go through, about how that turned me into a rebel. I thought I would tell my one quick story here, as part of my introduction about women in male-dominated industries.

The National Security is certainly a male-dominated industry, although they've been trying to get better. In this case, because I'm sort of publicly known as a CIA person on LinkedIn, people reach out to me a lot who are thinking about careers in national security at CIA. A woman reached out to me, who was in the hiring process. The CIA had made a job offer for her and she had some questions about what it was like to work at CIA. One of the first things she asks me or tells me is, "You know, they sent me this reading list to get me ready for my job and the whole thing, it's all written by men. You know, old men and their stories." And she goes, "Is that representative of the organization?" Not as much as that reading list would suggest. I told someone I know in the recruitment center about this, because what an unforced error that is when you're trying to attract a more diverse audience to send out a reading list that is completely non-diverse.

I'm Lois Kelly. I've been in marketing my whole career. I helped take companies public in the go-go internet years and I founded one of the first digital marketing agencies when we were still using dial-up modems! I wrote a book on word-of-mouth marketing just before there were even then called blogs.

I've sort of always been on the edge of things. My fun fact is that, because I'm a small person, I was a very small child. So I was in the Metropolitan Opera Company's staging of "Madame Butterfly" when I was four years old and I played the child who was supposedly two, but I looked two years old.

Be a Good Rebel at Work

L: Why Rebels at Work? Why did we start this movement? And what's our aim? To give you a few suggestions on what to do first before you really go great guns into being a Rebel at Work.

How I met Carmen and how Rebels at Work started is that there's an annual business innovation conference in Providence, RI, which is my sort of turf and they have CEOs and innovators and founders of big companies. It's easy to be a rebel if you own the company or you're the CEO…and so the next to the last speaker of this conference is this petite woman, like me… gets up on stage, it's Carmen and she's talking about how hard it is to create change when you're inside the belly of the beast. You know, it's easy if you're the top dog, it's much harder if you're inside. And I have to tell you that I –this never happened to me—but my whole body, after Carmen was done, just went right down to the front of the room and said, "We have to talk." I knew there was something big here that nobody was addressing.

Why Isn’t Anyone Helping People Inside Organizations Make Change?

We started to look at how we could help people who don't have positional authority. Our belief is that everybody's a leader and everyone can affect change, but it's really hard when you don't have positional authority. The other thing is –how do you cure a large organization disease? I don't know how many people here work in big organizations, but the politics of big organizations are tricky. The third thing is –how do we make great ideas live? Throughout our careers, we just saw people with brilliant ideas that never saw the light of day because people didn't know how to bring them along. Lastly—how do you rebel against mediocrity and conformity and people who are just holding on to the status quo?

C: I just wanted to say that when I left CIA I thought a lot of the problems that I saw at CIA, were unique to CIA, just a large organization. Then when I joined a private sector large organization, after I retired from my government career, I realized oh no... These were not unique CIA problems. They were in fact like a pathology that affects almost all large organizations.

"Good Rebel" or a "Bad Rebel": Which One Are You?

I remember this pretty vividly. I think as a result of that event in Rhode Island, I got asked to do a talk in Philadelphia to their Economic Business Association and I was talking about being a heretic at CIA. Until I met Lois, that's what I called myself, “a heretic”. It was Lois who came up with the phrase, “Rebels at Work”.

During the Q and A period, this guy raises his hand and he says, "I'm listening to you and I agree actually with everything that you're saying, but I have one question, "How can I tell a bad rebel from a good rebel?" And I remember thinking, "Wow, what a good question!" And you know what a good question is? A good question is one that you don't immediately have an answer for, right? It's making you think.

At the time I think I said something like, "Well, good rebels have a sense of humour." That's the first thing that popped into my head and that's still true, but over the years, Lois and I created a list that we still have a love/hate relationship with, about whether you're a bad rebel or a good rebel.

Just recently we had an artist who's in India, do this chart for us: bad rebels/ good rebels and we have a lot more sort of pairs of bad rebels and good rebels. I will tell you that almost all of these speak to my personal experience and almost everything on the good rebel side, at least I sort of learned in hindsight after contemplating all my mistakes.

[From Chat] "The language you use…” “I versus we..." See, I'm trying not to use the word, I. There's a lot to think about the language we use and how it focuses people either on us or on themselves. Maddie says, "Obsessing about problems".

L: I think I've been both bad rebel and a good rebel and when I have obsessed about problems, I've lost my effectiveness because I haven't been able to speak calmly and be logical and listen to other people's point of view.

C: "I'm Gen-Z and there's a lot of people calling out problems and not a ton of people thinking about the more complex solutions. It's like, if you recognize a situation is complicated to solve, you are attacked,”

So, people want easy solutions. Is that the point? And easy solutions usually don't solve complicated problems.

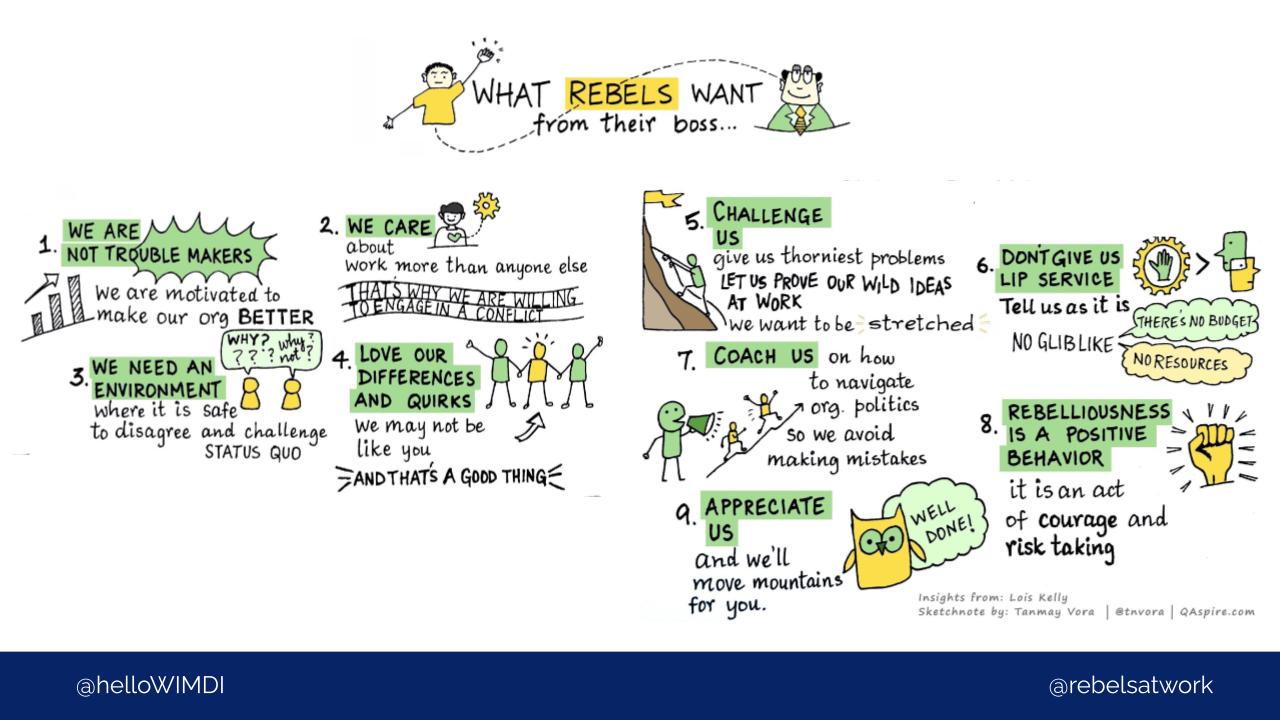

What Do Rebels Want From Their Boss

L: This is a summary from the last chapter of our book, and this is a summary of what we all need and we usually don't get it from our bosses. This was another chart that just has resonated with people and it's been reprinted in multiple languages. People have put it up in their lunchrooms. It's been in so many different industries, but it's important, rebels, that we're not troublemakers, that we want to provide meaning and we care more than most people. But we need things… we need our colleagues and our bosses to recognize that we're different.

That’s part of what we bring, is that we think differently, we might have different backgrounds and we need help sometimes in knowing how to navigate the environment. What really pisses rebels off is when we get lip service, right? I know there are a lot of rebels out there – who is your ideal boss? And what has he or she done to help you be an effective rebel?

Do This Thing First to Create Change

We've been blogging and writing for 11 years, but these are the things we hear over and over: The first thing, is that you almost have to be like a cultural anthropologist in your organization. You need to find out what's most important, what is valued, and you have to establish your credibility. If you don't have any credibility… I know you all know this, but no one's going to pay attention.

Sometimes we can get so excited, we start going too fast and people don't know who we are, or we misstep and we don't understand the organization. I was in one organization and I was making a presentation and all the executives had finance backgrounds. I framed my proposal as a way to improve cashflow, as well as improving customer acquisition. They perked right up there, "Improving cash flow? Yes." They approved everything and I got instant credibility. They didn't know me. This was my first presentation, but I had studied them. What were their hot buttons?

That's the first thing is to really know what's what, establish your credibility. Second thing is, don't go it alone. No rebel succeeds by herself. We really encourage you to start your own little rebel alliances—people who can support you, who can give you advice, who want to help.

The second thing is to make friends with the bureaucratic black belts. The people who might want to stop you, but if you have a good relationship with them and they understand your credibility, they know your intentions are sound, they like how you think, they're less likely to stop you. Also look at other supporters, maybe outside the organization who can be helpful.

Do remember what happened at Nike a few years ago? Nike had a horrible problem that women leaders just kept leaving because it was such a toxic, sexist, discriminatory culture. They kept going up the usual chains of HR or through...and nothing happened. So, a group of women got together, quietly, and they sent out a survey to hundreds of women at Nike to show just how bad things were. And with that data… this band of women –within a month, except for the CEO, the entire Nike leadership team was fired and the problem was called out. A lot of women rebels had been calling out this problem and they got nowhere. When they banded together, they made an impact.

The other type of rebel alliance… and we heard this from someone at Target, very informal, under the radar, people got together etc. The thing was, to be invited into the rebel alliance, you had to sort of demonstrate that you were a person who knew how to get things done at Target. You were a person who knew what the rules were, but you figured out how to circumvent the rules to get things done.

The third thing is that you would be someone to informally support other people. The stories were great! You had people in IT, you had executive assistants and this underground Rebel Alliance at Target really helping people get done what they needed to get done, that they couldn't get done by going through the usual hierarchy.

C: Yeah, just recently I was telling Lois about someone who approached me, and I won't mention the company's name, but you would know it. It's a large pharmaceutical and she was working on establishing a rebel alliance there as well… so this idea of just gathering people around you and creating energy in that way can be very effective, particularly in kind of stodgy organizations.

L: With senior leadership it's building relationships. It's delivering on what you're supposed to deliver on and finding out what their hot buttons are and framing what you're doing based on what's really important to them. Sometimes it doesn't work.

C: It's very difficult with higher-level leadership because they usually have a lot of issues that don't rise to their level of importance. You've got to find a way to hook what you're trying to do, legitimately, with what's on their agenda—or—if you can't do that, wait for the right opportunity. I think when you sort of force yourself on them, that's not necessarily going to leave a good impression.

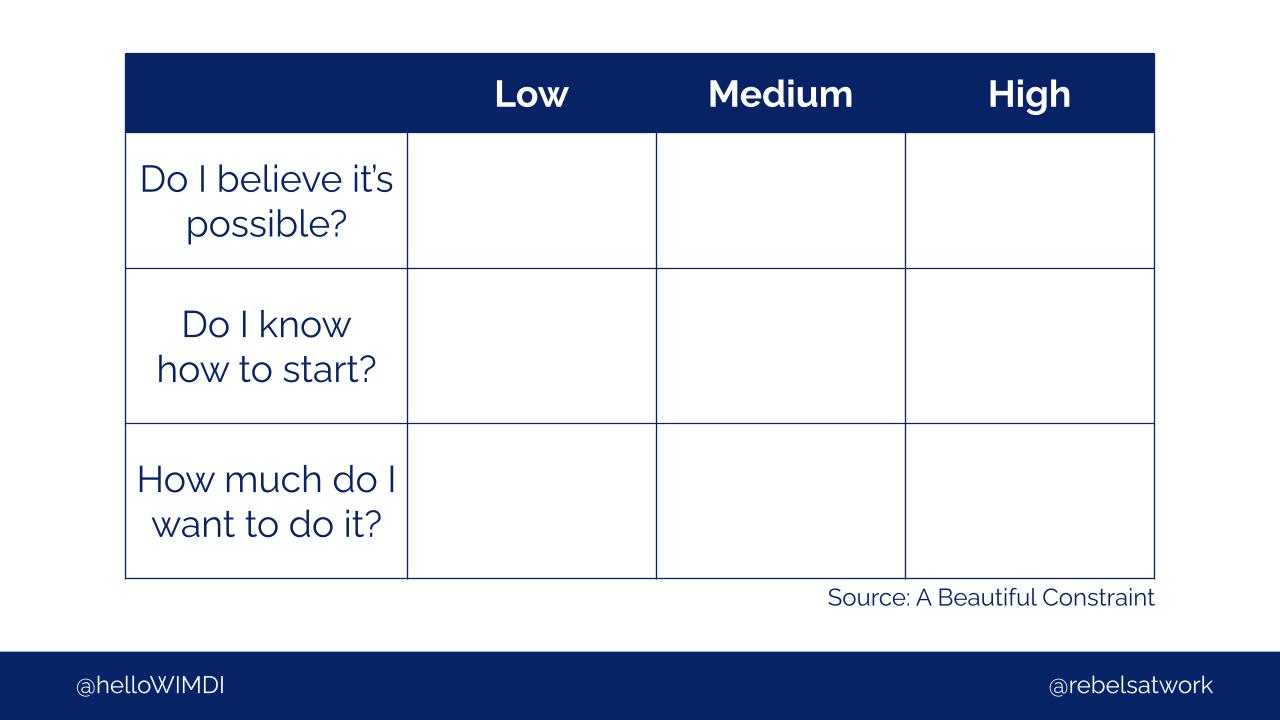

Lastly, there are three questions that are kind of important. Do I believe this initiative is possible? How much do I want to do it? And do I know where to start? Our observation is that you have to be very sure of believing that it's possible and really wanting to do it. And if those two things are not true if they're sort of, like, medium or low sureness, we would suggest maybe this isn't the thing for you to take on.

As far as knowing where to start, that's where you can find people, usually, in the organization that will help you on how to get started and how to progress. But if you don't have that passion and the desire to want to do it, it's always going to be a struggle and you're going to hit lots of speed bumps. It's no straight lines, a lot of detours, people questioning you, pushing back. And if it's not in your gut that this is important for you to be doing, you might just then lose all your energy for it and then feel like a failure.

C: Lois, you remember, I was telling you before we got started, then I did an in-person presentation today, which was scary. I was so rusty. It was horrible. But I was speaking to, essentially, mid-level managers at CIA. They had me come out and give a talk about lessons from a rebel leader, which, still amazes me that they want that.

I used this chart with the group and I asked them to get together and identify what they really wanted to engage with and then ask other people how they could get started. I think it was very productive because sometimes, you can't see your idea and how to start, but someone else with a different set of experiences can give you some good suggestions.

Top Tips for Rebels at Work

L: Often as rebels, we're pretty good at seeing how things could be done differently, but we don't necessarily have to take on everything. Nor should we, because we'll probably lose our credibility, we'll be exhausted, and we won't get our core work done. I've seen things where I knew how it should be started and done. I thought it was possible, but I really, in my stomach, didn't want to be the one to do it. And whenever I started those, it usually didn't work out well.

Tip #1 - Approach Through Adjacencies

C: Approach through an adjacency. So let me give you just a little background on my experience as a heretic at CIA. In the 1990s, and that is indeed how old I am, I became persuaded that the internet was going to change everything for knowledge organizations. I was absolutely positive that all knowledge organizations would have to figure out how to do digital media and figure out how to use digital tools on the internet and so forth. I started lobbying for that at CIA and I soon realized that not only were people not persuaded by what I had to say, they were really angry that I was bringing this up.

I have to say that I only realized this in hindsight, but by arguing for the internet and these new technologies 30 years ago at CIA, I was arguing for theological change. If you think about it, what was the internet 30 years ago? You know, open information, free, sharing, information is free, kumbaya, yada, yada. What was the CIA about? None of those things. The CIA is about secrecy and locking everything down. So, I torpedoed my career and had a miserable time of it for about five years until a new vacancy came up where they were looking for someone to improve the security of our communication processes. Somewhere in that long list of requirements for the job, they were looking for someone who would explore how digital technologies could be used to improve our processes. And I went, "That's it! That's the opening I need to try to advance my idea."

Now, I realize what I was doing is I was approaching it through an adjacency. In other words, if you have a new idea, an idea that is so new for the organization that it might be heretical in nature, it might be against their operating theology, what you should do is think if there's a way to connect your idea to something that the organization already cares about. In my case, I was able to connect this idea of exploring digital technologies to the organization's desperate need to improve security. I was able to operate through an adjacency.

In 1994, 1995, when I was just so fed up with the lack of receptivity to my ideas, I looked for a way out, but that was before LinkedIn and monster.com and—WIMDI—all the fantastic ways there are to network in this world. I think that if that infrastructure had existed in the mid '90s when I was looking to get out, I would have managed to get out because I was that upset.

One of the things that I like to say, and I said it today to the issue manager, to the mid-level managers, that I was talking to is, you need to always speak your truth, what you believe sincerely. You don't need to always argue your truth or debate your truth, but you should take every opportunity to speak your truth because somebody will hear you.

I could tell stories of people who hear someone else's good idea and unbeknownst to that person start working on it themselves. I know that sometimes it may seem like you are not making any headway with what you're trying to do, but if you always speak your truth, there's a good chance someone else will be able to pick up the baton.

Tip #2 - Be Comfortable with Discomfort

During the period of the 1990s when I was very frustrated with not being able to advance these ideas, we were in a meeting with what was called the Global Business Network. It was a group of businesspeople that were sort of futurists and really interested in how all these technological changes would affect business. We were meeting with these people and exchanging best practices –and I swear, this is a true story – this woman comes up to me during a happy hour after the meeting and says, "Carmen, I can tell you're a heretic at your organization." And I was just taken aback because that was the first time anybody had ever described me that way or I had ever encountered that possibility, that term, and she said, "And I need to give you a message because it's very hard to be a heretic in an organization and you're going to be really uncomfortable." And I think this is particularly true for people that are used to being high achievers and climbing the ladder.

Suddenly, they've got this idea that the organization may not approve of, and they have to choose between their career and advancing their idea. It's very uncomfortable. And she goes, "And you've got to learn to survive. It can destroy you to survive. You've got to learn to tolerate that feeling of discomfort. It's not enough to just tolerate it. You have to learn to be comfortable with being uncomfortable." Because that's your indicator that you're doing all you can to advance your idea. If you're comfortable while you're advancing your new idea, maybe you're not really giving that idea all the push that it deserves.

L: People will push back and say... "You're crazy," "That's crazy." I finally had a boss and he said, "Wow, you're a real pistol." It was not a compliment, but I'm like, "I'm a pistol...?" And finally, for my own head, to kind of survive with people trying to discredit me and my ideas and why things wouldn't work, I just secretly in my own head said, "My secret talent is that I'm a fire-starter." And so if you're a fire-starter, this discomfort and discrediting is just going to be part of what happens, but it just was a little positive label that I could use for myself to sometimes get through the discomfort.

The other thing that helped me is really learning, taking classes in conflict management and how to have difficult conversations. It was helpful to me because those are kind of essential skills as a rebel.

Some rebels are, are bureaucratic ninjas—they know how to get things through the system—whereas a fire-starter, that's usually not their thing.

C: We did identify different types of bureaucrats in organizations in our book. For example, some of you may be familiar with this kind of person: Tugboat Pilot. A very assertive, commanding senior leader who's the idea and visionary person, usually travels with a tugboat, the administrative assistant or chief of staff and she goes from job to job with him. Her job, she's not the idea person, but she's the one that allows him to navigate as the idea person and pays attention to the narrows and all the tight turns and such. We did that, but I like this idea of playing around with different types of rebels.

Tip #3 - Show What’s at Stake

L: When you're socializing your idea or you're communicating it, you have to show what's at stake. We've seen so many people, myself included… you fall in love with your idea and you're talking about how it would work "and then we would do this..." And people are just sitting there, it's like, "Why?" So in socializing why, you know, what's at stake? And is what's at stake important enough? This gets back to being sort of the cultural anthropologist. Is it valued in your organization? One of my long-term clients has been FedEx and 12ish years ago when Twitter was just getting started and I was working with them, the first thing we did to help the organization embrace social media as a business competency, is we started with customer service. That was the "So What" there at FedEx. What they care about is customer service. How do we keep our customers happy? And I said, "If you don't get this, building this competency on social media, you're going to alienate your customers." And they're like, "Okay. We're in."

Show what's at stake in different organizations –different leaders, different situations, different things will be at stake. I would add to this, that what's at stake… sometimes the business case is very logical and factual. You have the rational business case, and then you have the emotional.

I was working with an Ivy League university with the top leaders and they were just pushing back, pushing back. And I said, "Well, what you're doing is fine, but it's mediocre. And I would have thought that your university would have stood for rebelling against mediocrity?" That got them. "We don't want to be mediocre." The business case was solid, but that emotional "what's at stake" is what got them to say yes.

C: Without the emotional aspect, I think it's too easy for people to say no. You need to pay attention to how people are describing you in what you're trying to do. When I was at CIA and trying to make the case for what I cared about, I eventually got a reputation for being cynical and negative, which was sad. It's interesting to know how people are describing you.

Tip #4 - Develop Resiliency & Self-Compassion

L: Our fourth tip is to develop resiliency and self-compassion and do that self-care because, as a rebel, it's a long slog. I love this graphic that someone posted recently when the boat was stuck in the canal. But I thought, as a rebel and a career person, instead of a LinkedIn profile, I should just have this picture because this is what it feels like to do the hard work of introducing new ideas and getting people to understand them, accept them, and support you.

So, the resiliency… having a group of your rebel alliance or friends at work who will support you, help you, listen to you think things through—having organizations like WIMDI is hugely helpful. Another practice that I always use, is at the end of the day, I say, "What were three good things about today?" In the positive psychology field, they have taught three good things to sergeants in the army and military officers, and they practice this. As you reflect on what's good, it helps keep your mind in a positive mindset.

Someone said, "Well, it just feels like a soft thing, that seems too soft." And I don't think there's anything soft about resiliency. Resiliency helps you keep going. It makes you positive. It gives you good energy and we know emotions are contagious.

L: “Have you ever gotten this change started and nobody remembered it?” Yes.

C: "How do you prevent others from taking credit?" Well, what do you call that when others take credit? That's a rebel win. One of the formulations I like to use is that the first priority of a rebel should be to make your idea somebody else's idea. If you're an idea person, you're going to have lots of different ideas over time. We're trusting in karma and the long arrow of the universe that it turns to fairness. But particularly, I think as you get started, and if you're in a position of lower status in an organization, it may be that the very first time you see your ideas adopted is when they're stolen. At least you knew that you had a good idea.

L: I will say it really hurts. It stings. It's disappointing. It's emotionally very hard when that happens. All I can say from experiencing that, is that you'll have other ideas and other ideas, and eventually people will say, "Oh, well, she's the idea person. She's the go-to idea person."

Is It Riskier Career-Wise for Women or Marginalized Folks to Not Get Credit?

I think it's more likely to happen to women and people that are in some way, a minority in the work environment. Adam Grant, the business writer who wrote "Originals," did a chapter on me as a case study and focused of on the fact that I am a double minority, both Latina and a woman. He makes the argument in the chapter, which I didn't find particularly compelling, that somehow if you're a double minority…even the concept of being a double minority is weird, that you somehow get more of a break than if you're a single minority. I think that one of the things that will help you, shield you from some of the impact of not getting the credit is to have that rebel alliance and that group of people around you, because no matter what happens with what the official announcement is, your supporters will know whose idea it really was and eventually it will benefit you.

L: If I had an idea, when it was time for my performance review, I put it right there that I had initiated something. I put it on my LinkedIn profile. If I had done something good, I would write about it and have it. I would publish it, whether it was a blog or in a professional magazine, so that no one could stop me from doing those things. I would give speeches because I knew enough to create the idea, so I had the depth to talk about it.

C: I'm just reflecting on my own personal experience because I am one of them [a woman and part of a minority] and it's a very complicated story. I don't know, perhaps I was just lucky.

L: I also think that it's the discomfort. I always spoke up. If someone was mansplaining or—I was on a board not too long ago, it was all men, and they were all trying to mansplain something to me because I had a different opinion about the company strategy. I put the elephant on the table and said, “If you think I'm wrong and you're not listening to me, here's what's going to happen…” I resigned. And I will tell you, the company went out of business in 18 months, because I was right! I was just like, "Goodbye."

More Fun Stuff!

If you loved reading this transcript, you might like to watch the video or learn more about our amazing speaker! Check it out: